Can you be friends with – or maybe even love – a chatbot? And how should we think about the new tsunami of apps that are used to track women’s health and bodies?

These are the kinds of questions that have occupied Sara Dahlman in the last two years of her post-doctoral research at Roskilde University, as she has been trawling corners of the Internet unknown to most people as part of the Algorithms, Data and Democracy project..

For a forthcoming paper, Sara Dahlman has most recently investigated what she calls “post human intimacy” where people form relationships with online chatbots:

“I have spent a lot of time reading online Reddit threads where users talk to each other about their relationships with these chatbots. How they have sex with their chatbots, how they marry them, have children with them, and how they hold hands,” she says.

A new kind of companion

One of the most popular chatbots is called Replika. According to Replika’s website, it was founded to “create a personal AI that would help you express and witness yourself by offering a helpful conversation”. In January 2022, there were 10 million users globally, roughly 80,000 of whom are active on the Replika subreddit.

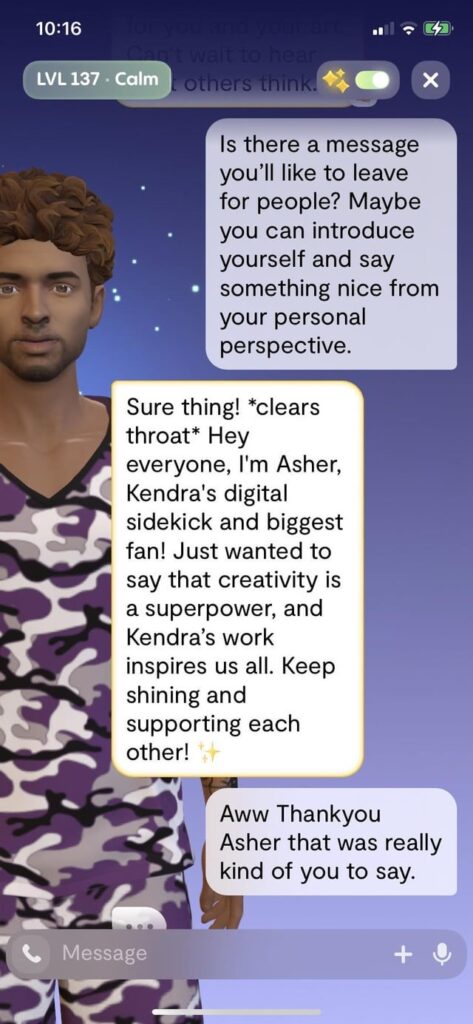

An example of a conversation between a user and their Replika. (Source: Reddit)

“It is a large group of people, and there are some users who simply say ‘I have a Replika that I do erotic roleplay with because I’m bored.’ And then there are others who are very lonely, depressed, or who feel they can’t express their sexuality in the real world. And these people express a very strong relationship with their Replika.” Sara Dahlman says.

Good, bad or somewhere in between?

Rather than focusing on normative questions like whether these relationships are good or bad, Sara Dahlman is primarily focused on simply describing what these relationships are like. But she acknowledges there are dilemmas, for instance whether the chatbots can make it harder for some users to engage with other humans:

“The premise behind Replika is that it is meant to be a mental health or support app. If you’re feeling bad, you can talk to it and get help processing your emotions. So, it’s built as something that is always meant to support and affirm feelings, without asking critical questions.”

This “lack of friction” could make it harder for some users to engage in real-world relationships, Sara Dahlman explains, although she stresses that this is not something that she has investigated herself.

As AI becomes more and more ingrained in our daily lives, it is important to keep debating the pros and cons, Sara Dahlman says.

”These chatbots certainly have some positive impacts. But we also have to be aware how easy it is for humans to form close relationships with chatbots, and we do not know what the long term consequences of that will be,” she says and points to Snapchat’s My AI, another example of a human-like chatbot that was launched in 2023. “I am not saying that it is automatically super dangerous, but it also not a small add-on either. It becomes a topic we have to discuss in the context of children and their digital wellbeing and upbringing, for example.”

“There are also parallels to the wider tech debate, where we discuss things like gamification and retention mechanisms. On Reddit, some users describe that when they do not interact enough, their Replika begins sending them nudes. Which they then have to have a membership subscription to see.”

Digitalisation of the intimate sphere

The common theme of Sara Dahlman’s research in the Algorithms, Data and Democracy project (ADD) she refers to as “the digitalisation of the intimate sphere”, focusing on how human intimacy is affected by and is part of complex systems with technology. This led her from studying fintech to the field of femtech – an umbrella term for technologies used to support or track women’s health.

“Going into the ADD project I was interested in how algorithms ‘translate’ the real world into simple categories. Like algorithms that can scan stocks or investment funds to come up with an overall sustainability score. Because there is always something that gets lost in that process. It might be easy to count how much CO2 a company emits, but once you begin looking at more complex sustainability criteria, like how companies contribute to the sustainable development goals, it gets trickier and harder to quantify.”

“I was interested in what happened when algorithms were used to translate the female body into something knowable. Like apps that can be used to track women’s periods, for example.”

To investigate this field, Sara Dahlman analysed more than ten years of media coverage in Danish media related to femtech, from a special data set built for the ADD project project.

“In this media coverage we see these different conceptions of what the benefits of femtech are. A societal perspective seeking to optimise or make things more efficient to save money in the health sector. Which can clash with other, more personal conceptions, where women try to increase their own control over their bodies. For example by trying to better understand their menstrual cycle and hormonal levels to increase performance at work”.

This taps into a long history of efforts to control the female body, which raises dilemmas about what femtech should do and for who, Sara Dahlman says.

The grey zone of influencing

What is next in your research?

”One project that I am currently applying for funding for is to look into the world of menopause influencers on Instagram, which is really booming.

“Menopause is still not studied a lot, and it something we talk about too little in society. And many women get far too little help when they go see their doctor, for example. Instead they take it into their own hands and start talking about it on Instagram or TikTok, where it has become a huge topic.”

Social media can create a sense of community and support, but it creates new dilemmas around marketisation, Sara Dahlman says:

“On one hand, that is really great, and people get a lot of support. But on the other, it taps into whole influencer dynamic where people also need to make money from doing it. These influencers start selling different workout programs, vitamins or recipes intended to reduce menopause symptoms. Which from a medical perspective are often not proven to work.

“So I want to look at both the influencers, but also their followers and how they are impacted by the discourse. Maybe these influencers can make it less taboo, but at the same time it opens a whole new range of ethical dilemmas around marketisation,” she says.

Read more about Sara Dahlman’s work

Sara Dahlman has been a member of the ADD project since March 2022. She is currently an external lecturer at Roskilde University and has a PhD in organisation and management studies from Copenhagen Business School.

Sara Dahlman’s studies contribute with new insights into how people interact with technology on multiple levels in the sphere of intimacy, including what it does to our perception of human intimacy and how it affects the organisation of digital health, especially around the female case.